By Muhammad Hamza

Humber College project management student Mo is a survivor of intimate partner abuse. It began in vague ways and then it escalated to become physical and humiliating.

“It was a toxic relationship,” they said. “Sometimes, I was used as a personal ashtray.”

Mo, who identifies as they and preferred being called by his first name for confidentiality, said it is really challenging sometimes to be in a same-sex relationship.

“It gets really hard sometimes. It got tough, especially in the relationship I was in,” they said. “My partner was a toxic person. They were not out. And our relationship was sort of a secret. When I was 17, my partner was 22.”

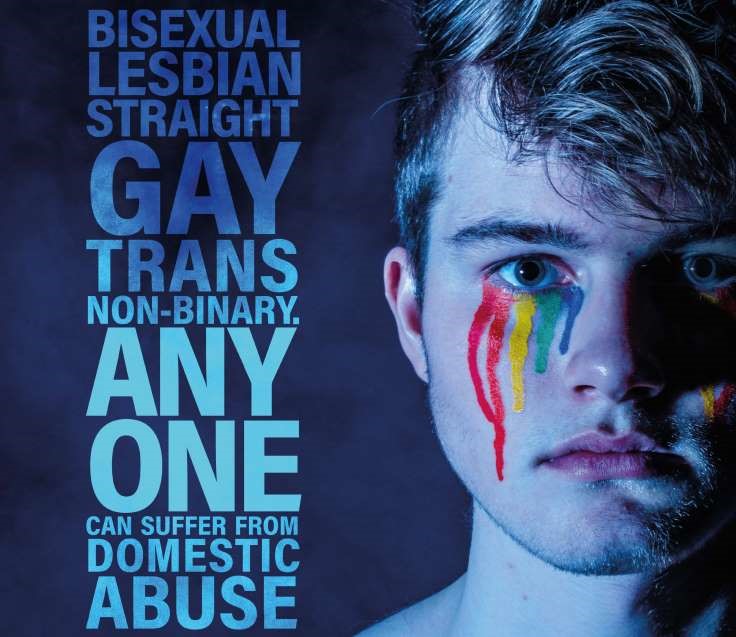

Intimate partner violence in the LGBTQ+ community is as devastating and destructive as that in the straight community. Abuse often thrives when victims become dependent on their partners, who exploit the power dynamic, leaving victims silenced by fear and unable to seek help.

Mo said they were too young to handle the situation and didn’t know how to separate themselves from their partner.

Mo said they faced physical abuse from his same-sex partner multiple times. Photo Credit: Pexels.com

They said they didn’t know if the situation they were experiencing was assault or harassment.

“And they started off with some really small red flags like flicking me in the head or, you know, pushing me around or telling me what to do,” Mo said. “And then it got worse and worse and worse.

“Since it was like a very toxic relationship and I was very young, I did not realize that what I was experiencing was harassment or assault,” they said.

The relationship was at its worst when Mo was objectified as personal property.

They said they were so blinded by love that they didn’t even bother to report the violence.

“And it was just like, blinded by the fact that I was so happy in a relationship, it kind of went to a point where I was hurt. I was like, I was used as a personal ashtray,” Mo said.

“Sometimes, like…” Mo pauses before saying, “I’ve got spots on my legs that represent cigarette burns.”

Mo said his partner had mental issues, and he was quickly angered.

“Like, he just had classic mental issues like he was. But I think he was bipolar. But I don’t want to blame it on that. It was purely about the fact that he got angry quickly,” they said.

After that traumatic eight-month relationship in which Mo suffered more violence in the last half, they started mental therapy to recover.

“I started therapy when I was 19 or 20. Like, I don’t remember when, but it was about that time,” they said. “I don’t think I joined any specific programs for it, but like my therapy did start with the idea of getting over the fact that, hey, my life is more than a relationship that I was in.

“And it kind of helped a lot, though,” they said.

Mo said that mental therapy helped them a lot in gaining confidence.

“It helped me gain myself, like gain confidence in myself, and like, some self-love here and there,” they said.

Statistics Canada reported in 2019, there were 22,323 incidents of same-sex intimate partner violence, or violence between same-sex spouses, boyfriends, girlfriends, or people in other intimate relationships, that were reported to the police in Canada between 2009 and 2017.

This accounted for about three per cent of all cases of intimate partner violence that were reported to the police during this time, it said.

The report said between 2009 and 2017, more than half, or 55 per cent of police-reported same-sex IPV, involved current or former boyfriends or girlfriends. Almost two in five, or 38 per cent, involved spouses, current or former, and the other eight per cent involved partners in other intimate relationships.

Males were more likely than females to be involved in major assaults, 18 per cent versus 12 per cent, the report showed.

Statistics in the study show police reported that 17 per cent of same-sex intimate partner violence involving male partners included a weapon, such as a knife, as compared to 12 per cent of incidents involving female partners.

The Statistics Canada report also said 35 per cent of victims of police-reported same-sex intimate partner violence who resided in rural areas asked that no further action be taken against their attacker.

Thirty-six same-sex relationship homicides occurred between 2009 and 2017, making up five per cent of all homicides involving intimate partners during this time, the report said.

Like Mo, Mary is another victim of intimate partner abuse who went to an emergency shelter after being in a violent same-sex relationship for two years.

Mary, whose real name is protected, left her abusive relationship and moved to Calgary with her daughter. Photo credit: Pexels.com

Mary and her nine-year-old daughter lived for three months in two emergency shelters before getting a long-term residence through Discovery House, a Calgary-based organization that offers a variety of services and long-term housing to assist women and children in rebuilding their lives after leaving an abusive relationship.

Anita Hofer, director of strategies and communication at Discovery House, said they provided a safer environment for Mary and helped her in her healing journey.

Anita Hofer said Discovery House offers services to more than 600 victims every year. Photo Credit: Discovery House

“She took her daughter in the middle of a winter night and came to an emergency shelter,” she said. “And from there, she came to Discovery House, and we helped her find long-term housing, get her settled into the community, and helped her get reintegrated into sort of a safer environment.

“And she was able to come and enjoy some of the programming where she could connect with other women who are in similar situations and really sort of rediscover herself,” Hofer said.

She said Mary has since left Discovery House and is now engaged in helping other survivors of domestic abuse.

“She had great dreams to actually go on and become a counsellor and do the same sort of work with other clients that she had been at that had been given to her from Discovery House,” Hofer said.

“So, she had a really great story, really one where she was able to grow and heal from the trauma that she had and go on to a life with her child that was like really wonderful and thriving in the community,” she said.

Hofer said the real challenge the LGBTQ+ community faces is that many people do not recognize that there is intimate partner violence in gay relationships.

“I think it’s about a lot of people don’t really realize that that’s a problem, right? That, this abuse, whether it’s control, financial abuse, physical abuse, whether it’s emotional abuse, it happens in all kinds of relationships, not just a man and a woman,” she said.

“We need to believe people, when they come to us and tell us these things are happening, we need to help them access the support that they need to leave that relationship safely, to develop a new community,” Hofer said.

The victims of intimate partner violence, whether in heterosexual or homosexual relationships, get help at Discovery House. The organization provides a range of services, from housing to mental therapy sessions, and prepares them for employment opportunities.

“We work with moms for up to a couple of years,” Hofer said. And just helping them get settled, helping them get counselling, helping their kids get counselling, helping them connect to employment, and helping them connect to postsecondary education, making sure that they’ve got money to live, pay the bills, buy groceries, get their kids in schools, and really just sort of reintegrate and become more interconnected with the community.”

Hofer said violence has a long-lasting impact on the mental health of victims and children.

Discovery House’s staff have certified training and understand domestic abuse and gender-based violence have severe implications for brain development, which is particularly important for children.

She said counsellors understand domestic abuse and gender-based violence have big implications for brain development, which is particularly important for children.

Discovery House supports more than 600 people every year, Hofer said.

The centre has staff that are social workers and counsellors. They have master’s degrees in counselling, some of them for the specifics of working with El, the LGBTQ+ community, she said.

Hofer said the organization has an Equity Diversity and Inclusion Committee made up of staff that are working to determine how they can better serve the LGBTQ+ community.

Discovery House also works with victims outside the shelter.

“Well, every year, it’s just over about 600 individuals. And so, we work with some of those in our shelter. And we work with some clients that are outside of the shelter as well,” Hofer said.

The federal government estimated in a 2018 report that an estimated 67 per cent of LGBTQ+ women have experienced at least one type of intimate partner violence since the age of 15, compared to 44 per cent among heterosexual women.

The report found 25 per cent of heterosexual women and almost half, or 49 per cent, of LGBTQ+ women, reported having experienced physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner since the age of 15, it said.

In 2018, one in five, or 20 per cent of LGBTQ+ women reported experiencing some type of intimate partner violence, which is nearly twice as many as heterosexual women (12 per cent), the report said.

Peel Regional Police believes it made significant efforts to address and combat intimate partner abuse in same-sex relationships, acknowledging the difficulties LGBTQ+ people confront and trying to create a safer and more welcoming environment for everyone.

In collaboration with the Safe Centre of Peel, police established a specialized Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) unit in 2021 to raise awareness of the problem, assist victims, and provide support and resources to those who have experienced violence and abuse in relationships.

“Peel Regional Police has a dedicated IPV unit that deals solely with IPV calls for service. All the assigned detectives and detective constables are given specialized training to assist them in investigating IPV incidents,” said Tyler Bell-Morena, a Peel police public and media relations officer.

“All the assigned detectives and detective constables are given specialized training to assist them in investigating IPV incidents,” he said.

Police are trained to spot or recognize signs of violence and abuse among victims, Bell-Morena said. He said investigators are skilled in performing threat assessments and offering vital assistance to Crown attorneys by submitting required paperwork that supports prosecutions involving high-risk offenders.

Bell-Morena said the intimate partner violence unit employs specialized analysts who keep track of and record all statistics related to IPV in the region.

Bell-Morena said Peel police address all victim challenges and ensure the safety of all victims through complete investigations, extensive safety planning, and victim management, along with the collaboration of community partners and resources provided.

“We would serve same-sex IPV victims at the Safe Centre,” he said. Police also include victim services provided by Indus and Hope 24/7, which have programming geared toward the LGBTQ+ community in Peel.

Various factors trigger intimate partner violence in homosexual couples, such as societal dynamics, power imbalances, and financial reasons.

Haran Vijayanathan, an LGBTQ+ rights advocate, said potential factors behind intimate partner abuse in same-sex couples may involve the consumption of alcohol and substance use.

“It’s the same reasons as in a heterosexual couple,” he said. “They could be a variety of reasons, from anger management issues to domestic abuse, alcohol, or substance use.”

Haran Vijayanathan, an LGBTQ+ rights advocate, said that intimate partner violence affects the mental health and well-being of people significantly. Photo Credit: Creatives Empowered

Vijayanathan, who is also a member of the LGBTQ+ community, said the impact of intimate partner violence on the victims is greater if they belong to an ethnic community.

“If you come from an ethnic community, like, for example, I always say that because I’m South Asian and I’m gay, my circle of community is very tiny,” he said. “Because, you know, the South Asian gay population is also quite small, so the chances of me running into the person who abused me that’s far greater within that community.

“And so how do you create social distancing and safe space creation? It’s quite limiting, right? And so, the opportunities for traumatization and re-traumatization occur on a regular basis,” Vijayanathan said.

He said domestic violence-related childhood trauma has an even bigger effect on a person’s adult life.

“Early adolescent or late adolescent, childhood trauma actually impacts your life as an adult, right? Especially if you don’t get the support that you need to help you work through the issues,” Vijayanathan said.

“And now people always say, ‘Oh, you’re gonna get over it,’” he said. “You don’t get over trauma.

Vijayanathan said the trigger could occur anytime and in unexpected places.

“You could be going grocery shopping, picking up milk or eggs, or whatever it is, and something triggers you at that point,” he said. “And you’re gonna experience all of that again, right?”

Vijayanathan shared his difficult upbringing in a home where his mother endured regular physical abuse from his alcoholic father. Eventually, the abuse extended to him and his sister, leaving a lasting impact on their understanding of relationships and trust.

“I come from a home where my mum was physically abused on a regular basis by my dad, who was an alcoholic,” he said. “And then he turned on to me and my sister. And so that kind of informs how we grew up as children and sort of what our relationship standards are.”

He said his experiences with his abusive father still deeply affected his ability to trust and navigate intimate relationships.

“And you know, he had an impact on me,” Vijayanathan said. “It’s very much the same thing in intimate relationships. You learn to trust someone, and you learn to live.

“It’s supposed to be loving, and you’re supposed to be sharing that,” he said. “But then, all of a sudden, you walk into that relationship with that level of trust and those expectations, and you become a punching bag to somebody. That’s totally a shock.”

Vijayanathan said the impact of intimate partner violence is the same on children, whether they are in LGBTQ+ relationships or heterosexual relationships.

“Again, whether it’s LGBT or heterosexual doesn’t matter,” he said. “Children still see what they see. And they experience what they experience, and that informs, so it becomes a sort of cyclical thing that becomes hard to break.”

He said victims of intimate partner violence in the LGBTQ+ community had a fear of calling the police because, historically, they didn’t have good relations with them.

“And then, when you look at the 2SLGBTQ+ community, that community has not had a really good relationship with the police service organization anyway, for from history, because of all the raids that happened in the baths and bars,” he said.

“We as a community were illegal, you know, until the ‘70s, I want to say, or the 80s,” he said.

The police do not understand that a man can rape another man, or a woman can rape another woman, Vijayanathan said.

“I don’t think many police officers understand that a man could rape another man, or a woman could meet another woman, or a trans person can rape another trans,” he said.

Vijaynathan said engagement with victims of intimate partner violence in the LGBTQ+ community may be improved by giving police personnel, sexual assault nurses and doctors, and sex crime units adequate training.

“And making sure that people are aware, I think that’s the best that they can do, by expanding the training for police officers, and on how they do intakes and have conversations with folks who are in abusive relationships from the 2SLGBTQ+ community,” he said.

Vijayanathan said sexual assault training should ensure that it’s done in an inclusive manner versus a derogatory manner.

“It’s a lot of systemic change, but also a lot of training and understanding, creating an understanding for people,” he said.

Leave a comment